I Have a Dream

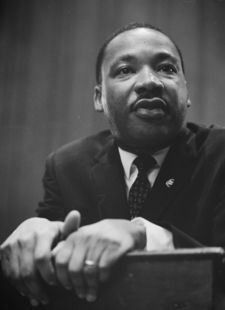

"I Have a Dream" is the famous name given to the ten minute public speech by Martin Luther King, Jr., in which he called for racial equality and an end to discrimination. King's delivery of the speech on August 28, 1963, from the steps of the Lincoln Memorial during the March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom, was a defining moment of the American Civil Rights Movement. Delivered to over 200,000 civil rights supporters,[1] the speech is often considered to be one of the greatest and most notable speeches in human history and was ranked the top American speech of the 20th century by a 1999 poll of scholars of public address.[2] According to U.S. Representative John Lewis, who also spoke that day as the President of the Student Non-Violent Coordinating Committee, "Dr. King had the power, the ability, and the capacity to transform those steps on the Lincoln Memorial into a monumental area that will forever be recognized. By speaking the way he did, he educated, he inspired, he informed not just the people there, but people throughout America and unborn generations."[3]

At the end of the speech, King departed from his prepared text for a partly improvised peroration on the theme of "I have a dream", possibly prompted by Mahalia Jackson's cry, "Tell them about the dream, Martin!"[4] He had delivered a speech incorporating some of the same sections in Detroit in June 1963, when he marched on Woodward Avenue with Walter Reuther and the Reverend C. L. Franklin, and had rehearsed other parts.[5]

Contents |

Style

Widely hailed as a masterpiece of rhetoric, King's speech resembles the style of a Baptist sermon (King himself was a Baptist minister). It appeals to such iconic and widely respected sources as the Bible and invokes the United States Declaration of Independence, the Emancipation Proclamation, and the United States Constitution. Early in his speech King alludes to Abraham Lincoln's Gettysburg Address by saying "Five score years ago..." Biblical allusions are also prevalent. For example, King alludes to Psalm 30:5[6] in the second stanza of the speech. He says in reference to the abolition of slavery articulated in the Emancipation Proclamation, "It came as a joyous daybreak to end the long night of their captivity." Another Biblical allusion is found in King's tenth stanza: "No, no, we are not satisfied, and we will not be satisfied until justice rolls down like waters and righteousness like a mighty stream." This is an allusion to Amos 5:24.[7] King also quotes from Isaiah 40:4-5—"I have a dream that every valley shall be exalted..."[8] Additionally, King alludes to the opening lines of Shakespeare's "Richard III" when he remarks, "this sweltering summer of the Negro's legitimate discontent will not pass until there is an invigorating autumn..."

Anaphora, the repetition of a phrase at the beginning of sentences, is a rhetorical tool employed throughout the speech. An example of anaphora is found early as King urges his audience to seize the moment: "Now is the time..." is repeated four times in the sixth paragraph. The most widely cited example of anaphora is found in the often quoted phrase "I have a dream..." which is repeated eight times as King paints a picture of an integrated and unified America for his audience. Other occasions when King used anaphora include "One hundred years later," "We can never be satisfied," "With this faith," "Let freedom ring," and "free at last."

Speech title

The speech, known as "I Have a Dream Speech", has been shown to have had several versions, written at several different times.[9] It has no single version draft, but is an amalgamation of several drafts, and was originally called "Normalcy, Never Again." Little of this, and another "Normalcy Speech," ends up in the final draft. A draft of "Normalcy, Never Again" is housed in the Morehouse College Martin Luther King, Jr. Collection of Robert W. Woodruff Library of the Atlanta University Center and Morehouse College.[10] Our focus on "I have a dream," comes through the speech's delivery. Toward the end of its delivery noted African American gospel songstress Mahalia Jackson shouted to Dr. King from the crowd, "Tell them about the dream, Martin."[11] Dr. King stopped delivering his prepared speech and started "preaching", punctuating his points with "I have a dream."

Key excerpts

- "In a sense we've come to our nation's capital to cash a check. When the architects of our republic wrote the magnificent words of the Constitution and the Declaration of Independence, they were signing a promissory note to which every American was to fall heir. This note was a promise that all men - yes, black men as well as white men - would be guaranteed the unalienable rights of life, liberty and the pursuit of happiness. It is obvious today that America has defaulted on this promissory note, insofar as her citizens of color are concerned. Instead of honoring this sacred obligation, America has given the Negro people a bad check, a check which has come back marked 'insufficient funds.'"

- "It would be fatal for the nation to overlook the urgency of the moment. This sweltering summer of the Negro's legitimate discontent will not pass until there is an invigorating autumn of freedom and equality. Nineteen sixty-three is not an end, but a beginning. Those who hope that the Negro needed to blow off steam and will now be content will have a rude awakening if the nation returns to business as usual."

- "The marvelous new militancy which has engulfed the Negro community must not lead us to a distrust of all white people. For many of our white brothers as evidenced by their presence here today have come to realize that their destiny is tied up with our destiny and they have come to realize that their freedom is inextricably bound to our freedom. We cannot walk alone."

- "I have a dream that one day this nation will rise up and live out the true meaning of its creed: 'We hold these truths to be self-evident, that all men are created equal.'"

- "I have a dream that my four little children will one day live in a nation where they will not be judged by the color of their skin, but by the content of their character."

- "I have a dream that one day on the red hills of Georgia the sons of former slaves and the sons of former slave owners will be able to sit down together at a table of brotherhood."

- "This is our hope. This is the faith that I go back to the South with. With this faith we will be able to hew out of the mountain of despair a stone of hope. With this faith we will be able to transform the jangling discords of our nation into a beautiful symphony of brotherhood. With this faith we will be able to work together, to pray together, to struggle together, to go to jail together, to stand up for freedom together, knowing that we will be free one day."

- "Now is the time to lift our nation from the quicksand of racial injustice to the solid rock of brotherhood. Now is the time to make justice a reality for all of God's children."

- "Let freedom ring. And when this happens, and when we allow freedom ring—when we let it ring from every village and every hamlet, from every state and every city, we will be able to speed up that day when all of God's children—black men and white men, Jews and Gentiles, Protestants and Catholics—will be able to join hands and sing in the words of the old Negro spiritual: "Free at last! Free at last! Thank God Almighty, we are free at last!"

Legacy

The March on Washington put much more pressure on the Kennedy administration to advance civil rights legislation in Congress.[12] The diaries of Arthur M. Schlesinger, Jr., published posthumously in 2007, suggest that President Kennedy was concerned that if the march failed to attract large numbers of demonstrators, it might undermine his civil rights efforts.

In the wake of the speech and march, King was named Man of the Year by TIME magazine for 1963, and in 1964, he was the youngest person ever awarded the Nobel Peace Prize.[13]

In 2003, the National Park Service dedicated an inscribed marble pedestal to commemorate the location of King's speech at the Lincoln Memorial.[14]

In 2004, the Library of Congress honored the speech by adding it to the United States National Recording Registry.

In popular culture

On the day King delivered his speech, two women, Janice Wylie and Emily Hoffert, were murdered in their Manhattan apartment. The case became known as the Career Girls Murders and included a young black man named George Whitmore, Jr being unjustly accused of this and other crimes. The case became the basis for the 1973 TV movie, The Marcus-Nelson Murders, starring Telly Savalas as police Lt. Theo Kojak, and was the pilot for the popular Kojak crime drama. The "I Have a Dream" speech is shown being broadcast on a TV set in the opening scenes of the movie; a young black man is beaten by the police in order to get him to confess to the crime; and this leads to the passing of the Miranda rights by the Supreme Court.[15]

Similarities to other speeches

The closing passage from King's speech partially resembles Archibald Carey, Jr.'s address to the 1952 Republican National Convention: both speeches end with a recitation of the first verse of Samuel Francis Smith's popular patriotic hymn "America" (My Country ’Tis of Thee), and the speeches share the name of one of several mountains from which both exhort "let freedom ring".[16]

Copyright dispute

Because King distributed copies of the speech at its performance, there was controversy regarding the speech's copyright status for some time. This led to a lawsuit, Estate of Martin Luther King, Jr., Inc. v. CBS, Inc., which established that the King estate does hold copyright over the speech and had standing to sue; the parties then settled. Unlicensed use of the speech or a part of it can still be lawful in some circumstances, especially in jurisdictions under doctrines such as fair use or fair dealing. Under the applicable copyright laws, the speech will remain under copyright in the United States until 70 years after King's death, thus until 2038.

References

- ↑ Hansen, D, D. (2003). The Dream: Martin Luther King, Jr., and the Speech that Inspired a Nation. New York, NY: Harper Collins. p. 177.

- ↑ Stephen Lucas and Martin Medhurst (December 15, 1999). ""I Have a Dream" Speech Leads Top 100 Speeches of the Century". University of Wisconsin–Madison. http://www.news.wisc.edu/releases/3504.html. Retrieved 2006-07-18.

- ↑ "A "Dream" Remembered". NewsHour. August 28, 2003. http://www.pbs.org/newshour/bb/race_relations/july-dec03/march_08-28.html. Retrieved 2006-07-19.

- ↑ See Taylor Branch, Parting the Waters: America in the King Years 1954-1963.

- ↑ "Interview With Martin Luther King III". CNN. August 22, 2003. http://transcripts.cnn.com/TRANSCRIPTS/0308/22/se.18.html. Retrieved 2007-01-15.

- ↑ "Psalm 30:5". Today's New International Version of the Bible. http://www.tniv.info/bible/passagesearch.php?passage_request=Psalm+30%3A5&submit=Lookup&kjv=yes&display_option=columns. Retrieved 2007-01-15.

- ↑ "Amos 5:24". King James Version of the Bible. http://www.biblegateway.com/passage/?search=Amos%205:24&version=KJV;. Retrieved 2010-01-13.

- ↑ "Isaiah 40:4-5". King James Version of the Bible. http://www.biblegateway.com/passage/?search=isaiah%2040:4-5&version=KJV;. Retrieved 2010-01-13.

- ↑ Hansen, D, D. (2003). The original name of the speech was, "A Cancelled Check," but the aspired ad lib of the dream from preacher's annointing brought forth a new entitlement,"I Have A Dream." The Dream: Martin Luther King, Jr., and the Speech that Inspired a Nation. New York, NY: Harper Collins. p. 70.

- ↑ Morehouse College Martin Luther King, Jr. Collection, 2009. Robert W. Woodruff Library, Atlanta University Center

- ↑ Hansen, D, D. (2003). The Dream: Martin Luther King, Jr., and the Speech that Inspired a Nation. New York, NY: Harper Collins. p. 58.

- ↑ Clayborne Carson "King, Obama, and the Great American Dialogue," American Heritage, Spring 2009.

- ↑ "Martin Luther King". The Nobel Foundation. 1964. http://nobelprize.org/nobel_prizes/peace/laureates/1964/king-bio.html. Retrieved 2007-04-20.

- ↑ "We Shall Overcome, Historic Places of the Civil Rights Movement: Lincoln Memorial". U.S. National Park Service. http://www.cr.nps.gov/nr/travel/civilrights/dc1.htm. Retrieved 2007-01-15.

- ↑ The Wylie-Hoffert Career Girl Murders by Marvin Smilon

- ↑ ""I Have a Dream" (28 August 1963)". The Martin Luther King, Jr. Research and Education Institute. http://mlk-kpp01.stanford.edu/index.php/kingpapers/article/i_have_a_dream_28_august_1963/. Retrieved January 19, 2009.

External links

- Audio of the "I Have a Dream" speech

- I Have a Dream Text, Audio, Video from AmericanRhetoric.com

- Deposition concerning recording of the "I Have a Dream" speech

- Lyrics of the traditional spiritual "Free At Last"

- SouthCoastToday.com: A read on a 4th, 5th and 6th graders' take on Martin

- MLK: Before He Won the Nobel - slideshow by Life magazine

- Footnote Martin Luther King Jr. - I Have a Dream - Page

- 47 Years Ago in Detroit: Rev. King Delivers First "I Have a Dream" Speech - video by Democracy Now!

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||